Rehabilitation and Participation Science

Program in Occupational Therapy

Author’s note: Initially, I sat down with David B. Gray, PhD, professor of occupational therapy and neurology, to discuss his career and accomplishments as part of our preparations for his upcoming retirement symposium, which was scheduled for the end of this semester. On February 12, however, he passed away unexpectedly. What began as a celebration of a brilliant career coming to an end has now evolved into a tribute to his life and work. – Kara Overton

Author’s note: Initially, I sat down with David B. Gray, PhD, professor of occupational therapy and neurology, to discuss his career and accomplishments as part of our preparations for his upcoming retirement symposium, which was scheduled for the end of this semester. On February 12, however, he passed away unexpectedly. What began as a celebration of a brilliant career coming to an end has now evolved into a tribute to his life and work. – Kara Overton

When talking about barriers and measures of participation for persons with disabilities, David B. Gray, PhD, was an expert. A lifelong learner and advocate for the disability community, Gray’s work involved asking questions, gaining an understanding within the communities he served, building coalitions and collaborations, transferring knowledge, and advancing the cause forward. His career spanned more than four decades and included countless accolades, honors and accomplishments. Those who knew him best admired his vision, his sense of determination, his love for his family, the mischievous spark he brought to the room, and the pursuit of excellence he inspired within others.

Throughout the course of our conversation, two main themes emerged from his reflection over his life and career. “When it’s all said and done, life has been about figuring out how to overcome obstacles, get good at something and then transition onto the next thing,” Gray said. “Just when you learn to navigate the hard stuff and begin to get comfortable, you transition into a new period that brings new challenges and adventures.” And through it all, he added, people influence your path along the way. “There’s a saying that says it’s not what you know but who you know, and I really believe that,” Gray said.

The road to excellence

Born the second of four children, Gray grew up in a tight-knit family in Western Michigan. His mother was a medical social worker, and his father was a physician who hoped to pass his private practice on to one of his children. Always a bit of a rebel and independent thinker, Gray had other ideas. Following high school graduation, he chose to attend Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin, where he received a very abrupt wake-up call right from the start. “The outstanding success story from my time in undergrad is that I made it out alive,” laughed Gray. “My first paper came back with a note on it that read, ‘D – and that is a gift – see me.’” That moment captures the overall sentiment and paints a picture of his experience in undergrad. “Lawrence was a really tough school,” Gray said. “It was the first time in life that I had to really work at something to be successful, but it was those habits and routines that developed as a result of the hard work that would later serve me well amid the challenges that would follow in my life.” While at Lawrence, Gray met his wife, Margy. “I was the last to show up for a class one morning, and there was only one seat left, which happened to be between a beautiful blond and a beautiful red head. Tough spot,” he quipped with a wink and a smile. A few casual exchanges with the “beautiful red head” turned into more; Margy and Gray dated throughout their time at Lawrence and married following graduation.

After completing his bachelor of science degree in psychology, Gray moved on to pursue his master’s degree in experimental psychology at Western Michigan University in Kalamazoo. In contrast to the rigorous and academically challenging curriculum present at Lawrence, Gray found Western Michigan to be much less demanding. Shortly after beginning the program, Gray and his wife welcomed their first child, David, in the fall of 1967. Two years later, their daughter Elizabeth was born. Upon completing his master’s degree in 1970, Gray opted to leave his role as an instructor of psychology at Seton Hall College so that he could pursue his doctorate degree as a full-time student at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

Pursuing the PhD: The road less traveled

Upon entering the PhD program in psychology and behavior genetics at the University of Minnesota, Gray again found himself facing academic rigor. The program was fiercely competitive – accepting only four students per year – and was ranked the top program of its kind in the country. While the program itself was known for excellence, Gray made personal connections while there that would later transform his life. In particular, he met Travis Thompson and Sheldon Reed, PhD. Thompson was his primary advisor and Reed was the director of the Charles Fremont Dight Institute for the Promotion of Human Genetics at the university. Both men pushed Gray to excel during his time in the program, and later became lifelong friends and colleagues.

After a challenging four years, Gray earned his PhD in 1974, and accepted a role as the Director of Behavior Modification at the Mental Retardation Center of the New York Medical College in Valhalla. Shortly after moving his family to the East coast, Gray and his wife welcomed their third child, Polly in 1975. Even as the Grays settled into their new home, they began to consider moving back to the Midwest. In 1976, Gray accepted a position at the Rochester Social Adaptation Center in Rochester, Minnesota, and they returned to raise their young children near their own families.

The detour and defining moment of 1976

Initially, upon moving back to Minnesota, the Grays rented a house while waiting for theirs to be built. Once their new home was near completion, they moved in and worked on it themselves to reduce costs. On a rainy day in July of 1976, Gray’s life was forever transformed. The contractor had neglected to cover a portion of the roof that was being worked on, and rain was dripping through the ceiling. Gray went up to cover the hole, and in the process of coming back down, he slipped, fell and broke his neck. The accident left him paralyzed and drastically changed the course of the life that he and Margy had planned for themselves.

Initially, upon moving back to Minnesota, the Grays rented a house while waiting for theirs to be built. Once their new home was near completion, they moved in and worked on it themselves to reduce costs. On a rainy day in July of 1976, Gray’s life was forever transformed. The contractor had neglected to cover a portion of the roof that was being worked on, and rain was dripping through the ceiling. Gray went up to cover the hole, and in the process of coming back down, he slipped, fell and broke his neck. The accident left him paralyzed and drastically changed the course of the life that he and Margy had planned for themselves.

Following the accident, Gray spent an entire year in inpatient rehabilitation, undergoing numerous procedures and countless therapy sessions. For 365 days, he was thrust into ongoing medical treatment that was filled with discomfort, pain and constant trials. It was his first experience being on the receiving end of the health-care spectrum, and one that was forever etched into his mind. People began to treat him differently and many fell out of his life altogether. “That type of situation is hard for people to process,” Gray shared. “Many people just don’t know how to respond to a change that significant. While there were several people who stepped out of my life, there were many others who stepped up in very impactful ways. Dr. Reed, one of my PhD mentors from the University of Minnesota, sent my family $100 a month for three years following my accident. It was such an incredible act of generosity, and a gesture I will always appreciate. Others visited regularly, throughout my stay in the Mayo Rehabilitation Unit and also after I returned home the following year.”

When Gray returned to work the following year, he faced new challenges in his profession. He moved into a role as the director of research at the Rochester State Hospital, but Gray noted that he was treated very differently than prior to the accident. Travis Thompson, his friend and colleague from his time at the University of Minnesota, stood by his side during this incredible time of transition. Upon learning of Gray’s predicament and unhappiness with his work, Thompson, who worked for the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in Washington, D.C., notified him about an opening at the NIH. Shortly thereafter, following a series of successful interviews and significant discussion with Margy, Gray and his family moved to D.C. and he accepted a role in the Office of Scientific Review of the National Institute for Child and Human Health Development (NICHD) within the NIH. It was a limited-time position, intended to last for only a year, but it was a new beginning for Gray and his family.

Full speed ahead: Leading the way in Washington, D.C.

Gray described the NIH as a highly complex and efficient government operation with an extensive set of rules and policies. Within his year there, he met several people who helped him navigate the NIH and mentored him along the way. “They have a highly systematic way of reviewing the applications for funding and awarding the research money,” Gray said. “Once you learn the system, it’s incredibly impressive to watch.” It was an environment that Gray appreciated, and he quickly adapted to the culture and took advantage of the opportunities available. Following his first year there, and the completion of the project, he moved into a permanent role as a health scientist administrator within the human learning and behavior branch of the NICHD. During his time there, he helped develop a scientific learning disabilities program that experienced significant growth and increased grant funding from $800,000 to several million dollars in a four-year period.

Within those four years, Gray became very active in the disability movement that was underway. He formed powerful connections with people who were at the heart of the movement in the hub of our nation’s capital and emerged as an insightful voice, advocating for the civil rights of people with a disability. Through his networking and advocacy initiatives, he became good friends with Justin Dart and Evan Kemp, who were both proponents of the disability movement. “It was an amazing time to be in D.C., and to be a part of what was happening in the world around us,” Gray said. “Regardless of how you get around in society, whether you roll along the sidewalks in a chair or otherwise, you have a right to be heard and treated equally.”

Following recommendations by Senate and House members, advocacy by former directors, and concerted efforts by leaders of the disability community, Gray was recommended for a presidential appointment by former President Ronald Reagan in 1986. He soon accepted the role of Director of the National Institute on Disability and Rehabilitation Research (NIDRR) for the U.S. Department of Education.

While Gray’s transition to the NIH was seamless and natural, his move to NIDRR was quite the opposite. The U.S. Department of Education had a completely different process than anything that was in place at the NIH, and the funding was granted in a much less systematic way. “It was no secret within the NIH that the department of education operated very differently. I had been cautioned before accepting the appointment that NIDRR was quite different, and was beginning to have doubts about the move, but I went ahead with it,” Gray said. He laughed and affirmed the decision with his characteristic wit, “I mean, it was a presidential appointment; how do you turn that down?”

Once he immersed himself in the role, he discovered that his concerns were warranted. It was challenging, stressful work, and one of the most difficult roles he held during his career, although it only lasted a year. “Of all of my experiences, my time at NIDRR is one of the things I’m most proud of. It was by far the hardest; I was working nonstop day and night, but I did it and I pushed myself to succeed,” he said. A year later, he transferred back to the NIH after accepting positions in the mental retardation and developmental disabilities and the human learning and behavior divisions.

At that point, a need arose for the development of a new organization that would be devoted to the advancement of research in medical rehabilitation, separate from anything the NIH or NIDRR were doing. In 1991, the National Center for Medical Rehabilitation Research (NCMRR) was created, and Gray was named acting deputy director of the initiative. The NCMRR was tasked with fostering the development of scientific knowledge needed to enhance the health, productivity, independence and quality of life of people with physical disabilities. Gray was instrumental in overseeing the organization’s operations and helped select the board members for the group. One of those board members was Carolyn Baum, PhD, OTR, FAOTA, Elias Michael Executive Director of the Program in Occupational Therapy at Washington University. For four years, Baum and Gray worked together on the NCMRR, advocating for the disability community. Eventually, after several attempts, Baum recruited Gray to the Program in Occupational Therapy. “I kept telling him that he could do great things with our Program,” shares Baum, “and that when he was ready to quit being a bureaucrat, he should come to St. Louis. I knew he could truly make a difference by combining his expertise with ours in the occupational therapy world, and that together, we could change lives.”

The move to St. Louis

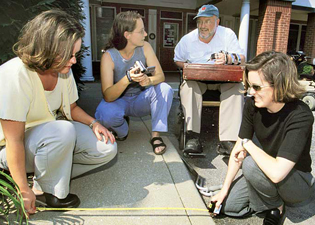

Gray came to the Program in 1995. “It took me a while to figure out what I wanted to focus on,” Gray said. “I had spent many, many years reviewing research proposals and requests for grants and funding, but had never actually written my own.” He discovered his niche when he began to focus his work on mobility impaired individuals and the environmental support and factors that impact participation. He received numerous grants from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), NCMRR and NIDRR for his work, and completely revolutionized the science behind occupational therapy by introducing a focus on outcome measures. In 2004, his research team developed the Community Health Environment Checklist, or CHEC, as an assessment tool to measure whether or not a location was truly usable to persons with a specific impairment. Developed around the ADA accessibility guidelines, the list enables occupational therapists and students to objectively assess locations based upon the priorities of people with mobility, visual or hearing impairments. The CHEC has been used to create online maps that provide information about the usability of community sites to people with disabilities, and has become a tool utilized by students and professionals throughout the country. CHEC maps can be located at www.checpoints.com.

Gray came to the Program in 1995. “It took me a while to figure out what I wanted to focus on,” Gray said. “I had spent many, many years reviewing research proposals and requests for grants and funding, but had never actually written my own.” He discovered his niche when he began to focus his work on mobility impaired individuals and the environmental support and factors that impact participation. He received numerous grants from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), NCMRR and NIDRR for his work, and completely revolutionized the science behind occupational therapy by introducing a focus on outcome measures. In 2004, his research team developed the Community Health Environment Checklist, or CHEC, as an assessment tool to measure whether or not a location was truly usable to persons with a specific impairment. Developed around the ADA accessibility guidelines, the list enables occupational therapists and students to objectively assess locations based upon the priorities of people with mobility, visual or hearing impairments. The CHEC has been used to create online maps that provide information about the usability of community sites to people with disabilities, and has become a tool utilized by students and professionals throughout the country. CHEC maps can be located at www.checpoints.com.

In 2005, Gray was instrumental in securing funding through the Missouri Foundation for Health for the development of the Health and Wellness Center at Paraquad. As a fully accessible gym in the St. Louis area, the center serves as a resource to eliminate barriers and help promote overall physical health and emotional wellness for persons with a disability. “David Gray was a phenomenal scientist and was largely responsible for helping our Program and community advance forward in truly significant ways,” Baum says. “His work has made a lasting impact, and we owe him a tremendous sense of gratitude for all that he’s done for us.”

Gray has also impacted lives outside of the research lab. As a teacher, mentor, and friend, Gray made a difference in the lives and professional development of countless students. Carla Walker, OTD ’14, OTR/L, had the opportunity to work alongside Gray in a variety of capacities, and credits him with helping channel her professional course and development. “I appreciated Dr. Gray’s unwavering focus on what is needed rather than what is easy. He was a visionary who led our team to make a difference through programs and research that have improved the lives of the disability community on a local, national and international level.”

Kerri Morgan, MSOT ’98, OTR/L, agrees. “Dr. Gray influenced minds, policy, programs and rehabilitation processes through his leadership, science and advocacy for disability. He was a big thinker and conceptualized research ideas that were usually way ahead of his time.” Like Walker, Morgan also credits Gray for the impact he had not only on the disability community itself, but on her personally.

“I selected him as my master’s mentor not because he had a disability, but because I had an interest in his work and ideas. He ended up serving as more than just my master’s advisor, but ended up mentoring me in living life successfully with a disability.”

While his time in Washington, D.C. gave Gray some of the most memorable moments of his career, his time at Washington University certainly offered some of its most rewarding experiences. Gray touched countless lives and made an impact beyond measure for so many people, including former students, colleagues and persons with a disability and their family members. The Program in Occupational Therapy will certainly not be the same without him, but it, along with the communities it serves, will be better because of him. “Dr. Gray built a team of professionals and sent accomplished students into the field for many years. They will continue to have an impact on communities throughout the world,” says Walker. “His legacy is true change and opportunity for meaningful participation among persons with disabilities.”

We welcome inquiries from prospective students, potential collaborators, community partners, alumni and others who want to connect with us. Please complete the form below to begin the conversation.

Schedule an Info Session

We are excited that you are considering applying to the Program in Occupational Therapy at Washington University. Please join us for a Zoom Information Session for either our entry-level MSOT or OTD degrees or our online Post-Professional OTD. Current faculty members will discuss the degree program and answer any question you may have. We are offering these sessions on the following days and times. The content is the same for each one, so you only need to sign up for one.

Upcoming ENTRY-LEVEL Degree ZOOM Info sessions:

Schedule an Entry-Level Info Session

Upcoming PP-OTD Degree ZOOM Info session: